I am most grateful to Bob Stansberry, a busy rancher, for taking the time to write out this description of processes that would be otherwise unknown to most of us and to posterity.

From #41 of the Mattole Valley Historical Society’s Now… and Then,

“Tanbarking in the Mattole Valley,” by Bob Stansberry

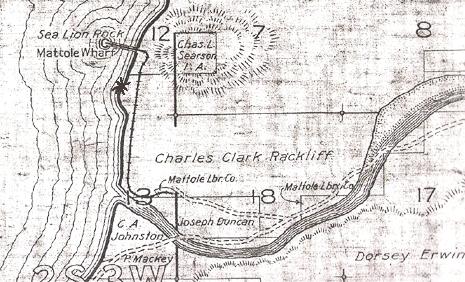

In 1952 Metten & Gebhardt, a leather tanning company based in San Francisco, entered into an agreement with my parents, John and Clarice Stansberry, to harvest the tanbark on a part of our ranch. They contracted the peeling of the bark out to a fellow by the name of Nelson Miles. The following year, in 1953, Metten & Gebhardt again acquired the right to harvest bark, this time across the Mattole River and on the east side of the ranch. This time they contracted the work to Henry Chapman and his sons, of Phillipsville, Calif. They paid us $8 per cord for the bark that was harvested.

In the summer of 1949 the folks had hired John Buxton to bring in his Allis Chalmers bulldozer (which at the age of four I referred to as “Old Biggy”). With my uncle Arch Smith—who was an expert at blasting out rocks and stumps with dynamite (referred to as a “powder monkey”)—they built access roads to haul the bark out.

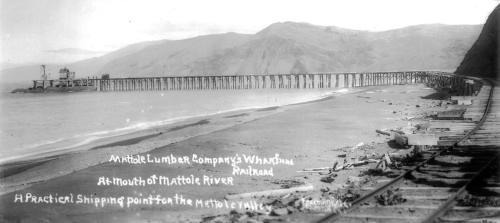

Checkie Chadbourne said that he drove a “bob tail truck” (truck without a trailer) out of this area hauling bark, after the closing of the extract plant at Briceland and when shipping out of Shelter Cove was discontinued. Most of the bark from the Upper Mattole was trucked to the railroad station at South Fork, Calif.

In 1946, our neighbor Lee French, who had a ranch at Ettersburg, Calif., purchased a 3-ton International truck. He equipped it with a flatbed and racks to haul lambs, wool, and equipment, for himself and neighbors. He also built a smaller bed with side stakes that he could exchange with the bigger bed, thus enabling him to access the narrow tanbark roads. Lee had a D-2 Cat of his own by this time so he built a wooden sled with steel runners to tow loads of bark out of the woods behind the Cat. He thrived on work!

His son Richard remembers going with his dad to Gary Svendsen’s property on Wilder Ridge to load bark that Gary had peeled and stacked. The bark was loaded by hand, often on a hot afternoon. After a tier of bark was partially stacked on the truck, a rope was tied between the stakes on top of the bark to keep them from spreading. After that the tier of bark was completed. Once the truck was loaded with several tiers of bark (two and a half to three cords) it was taken to South Fork. Richard remembers swamping (tossing) bark back in the hot boxcars. Crew working for the Wagner Leather Co., based in Stockton, Cal., who had a refinery in Briceland, besides holding extensive tanoak timber acreage in southwestern Humboldt. Center front with tilted hat is probably Earl Harrow; kneeling front left probably young Jess Stansberry. Photo from Harrow family via Bob Stansberry.

Crew working for the Wagner Leather Co., based in Stockton, Cal., who had a refinery in Briceland, besides holding extensive tanoak timber acreage in southwestern Humboldt. Center front with tilted hat is probably Earl Harrow; kneeling front left probably young Jess Stansberry. Photo from Harrow family via Bob Stansberry.

Before the advent of the bulldozer (crawler tractor with blade mounted in front), these bark roads were built with hand tools, dynamite, and horse-drawn equipment (side-hill plows, “V” scrapers, and drag scoops). Lee French said that it took three men to reopen a road in the Spring after the winter rains had caused the inside road bank to fall in: “One to drive the team, one to run the plow, and one to hold the plow beam over against the bank.”

Steve Baxman from Fort Bragg, Calif., told me that he brought the first blade “Cat” into the Mattole to build tanbark roads. This was in the late 1930s. He said that they unloaded it off the low-bed truck in the redwoods near Bull Creek and that it was a long slow trip “walking” it (driving it) over the mountain to Honeydew.

It was about this time, in the 1930s, that John Chambers of Petrolia purchased a D-4 Caterpillar. It was the first blade tractor owned in the Valley and is still used by his grandson, Kelton Chambers. Johnny said that he used to walk it up the valley and build roads for neighbors. At mid-valley, near Honeydew, Lee French would rent it and take it on to Ettersburg, building roads for people along the way. Lee said that while building the road up Crooked Prairie ridge for his neighbor Rod Hinman, Rod somehow got his hand caught between the cable attached to the Cat and a log that they were pulling. The only way he could free Rod’s hand was to cut the cable with an axe. Lee said that “with each blow of the axe Rod would let out a squall.”

Tanbark peelers, from the impressive Mary Rackliff Etter collection. Photographer unknown [Edit: Ray Jerome Baker took this photo and the next]

Tanbark peelers, from the impressive Mary Rackliff Etter collection. Photographer unknown [Edit: Ray Jerome Baker took this photo and the next]

My first and only real memory of the actual peeling of a tanoak log was in the Spring of 1952. Dad and I came along on the road where a couple of young fellows had cut down a tanoak tree and were peeling it. Dad had worked as a bark peeler when he was young, as did his brothers (his sister Mabel had cooked in a bark camp), and he felt a need to show these fellows how it was done. As I remember it, he took the axe and laid it lengthwise on the log, this plus the depth of the axe blade gave him about four feet of measurement as was required. After measuring he went about chopping away a narrow ring of bark around the log with the vigor that he always applied to his work.

After the log was ringed at four-foot increments, the bark was split or scored lengthwise and peeled away from the tree in large slabs. These slabs were left near the log where they would dry and curl up like big cinnamon sticks. Later in the season, the bark was packed by mules or sledded to the nearest road and stacked to be loaded on trucks (or wagons in the early days).

Cables moved this wagon of tanbark over steep slopes.

Cables moved this wagon of tanbark over steep slopes.

Bark peeling season began in the Spring (May, June, and July) when the sap was flowing and the bark would separate from the log easily. Charlie Etter said that after you cut the tree down you wouldn’t even stop work for lunch because the bark would tighten to the log after the sap couldn’t flow.

Before felling a tanbark tree, the bark was peeled away from the ground up to four feet. This is where the thickest bark is. Sometimes smaller trees were just peeled up eight feet and left standing; this was called “jayhawking.” Felling was done with axes and two-man “misery whip” handsaws (though in the 1950s chainsaws came into use). Dunnage was probably laid down for the tree to fall on, thus making it easier to roll the log and to access the underside of it. After the bark was removed, the remainder of the tree was left in the woods to rot, though I do remember a large stack of peeled tanoak wood by our house.

Before World War II, most young men of the Mattole worked in the bark woods at some point in their lives. Al Hadley said that he and a friend once walked from Honeydew through the mountains to Elk Ridge east of here because they had heard that they might be able to get a job in the bark woods over there. The Smith boys (Paul and/or his brothers Tom, Steve, and Robert) peeled on the Etter property in the Fourmile Creek drainage between Honeydew and Ettersburg; their broken car of a 1920s vintage still remains in the woods there. Frank Landergen also had a “bark show” in the Fourmile Creek area. Kenny Wallen of Miranda, Cal., said that when he was a kid he and his father peeled bark in the Dry Creek area east of Honeydew and on Bear Trap Ridge south of Honeydew. They employed one mule to pack the bark out of the woods. Earl Harrow once showed his old arthritic hands to me, all bony and rough from wielding an axe when he was young. Ken Roscoe said that these were the fellows you looked for when putting together a baseball team because they had strong arms and good upper body strength.

The bark crews usually camped in the woods near their work and usually by a spring. Some of these camps can still be found, evidenced by an old steel bedframe with a tree growing through it, an old crosscut saw, or a pile of tin cans and an old coffee pot. (Nelson Miles’ crew had a pig pen where they kept pigs to feed the scraps to.) Cousin Bill Lee remembers the chipmunks coming into Nelson’s camp looking for food handouts.

Earl said that when he was working, the job of cooking went to the first guy that complained about the food. Once the guy cooking (tired of his job) decided to load the food down with salt. One of the fellows eating says, “Damn, this is salty!,” then he catches himself and says, “but that’s just the way I like it.”

As with anything, the bark business could be fraught with difficulties. I remember that Mr. Miles brought in a couple of half broke mules and tried hitching them to the sled to bring bark out to the road; they bolted and tore his harness to pieces. In another instance, one of his workers caught the woods on fire with the new-fangled chainsaw. But worse was the big fire that burned the north side of the Fourmile Creek drainage and all of the bark that Nelson had stacked along the road. Bill Woods remembers when he and his step-father, Clarence Stansberry, had the job of peeling and getting the bark out of the big canyon just west of the Industrial Park between Garberville and Redway. They borrowed a mule from Clarence’s brother Johnny Stansberry. The mule soon figured out that he could get out of work by laying down and rolling off the trail, with a load of bark on. After a couple of sessions of this, Bill said, “Dad went down there and walked all over that mule with his cork (calked) boots, and the mule never tried that again.” Some of these mules got so they would go to and from the woods without guidance.

The bark industry was a way for folks in these hills to make a few dollars. Our neighbor, Mrs. Gibson, would go into the woods after the peeling and sack up the bark chips because they could be sold also.

All of this ended in the mid-1950s, replaced by a chemical process for tanning leather and a lack of demand for bark-tanned hides. •

Mules bound for a wagon or truck with their tanbark loads, crossing creek in Honeydew. Photo courtesy the Etter family.

Mules bound for a wagon or truck with their tanbark loads, crossing creek in Honeydew. Photo courtesy the Etter family.

A few more thoughts on the business from Laura… What happened to the market for tanbark?

Roger Brown told me that he peeled tanbark in the Mattole Valley in the 1950s. So the business did not entirely disappear until decades after the boom was over. But as previously noted, the tanbark forests of the Mattole Valley were not infinite. Their trees had only come into high demand as the woods around population and trade centers such as the Bay Area were depleted; and as the supply around Southern Humboldt in turn shrank and the chrome (chemical) methods became more common, tanbark harvesting contracts here dropped off.

I found the following info at this internet site:

https://ventana2.sierraclub.org/santacruz/node/216

“A statement written by Susan Lehmann for the City of Santa Cruz Planning and Development Department says that… ‘prodigious amounts of tan bark’ had to be used. ‘Not just the bark but the entire tree was harvested and used for barrel staves as well as firewood to produce steam to run the plants. Although the supply seemed endless, by the turn of the century the oak trees, like the redwoods used for lumber and to fuel the limekilns, were seriously depleted, bringing about the eventual demise of the industries they had created.’

“A diagram in Willis Linn Jepson’s book Tanbark Oak and the Tanning Industry [published 1909] shows the number of cords of tanoak used for tanning in California from the years 1851-1907, with 4-6 trees per cord. The number of cords per year increased over time to add up to a total of 1,722,000 tanoak cords used in that 57 year timeframe. Estimating on the low end at 4 trees per cord, that adds up to 6,888,000 trees felled in California for tanning leather, just within the dates listed (Jepson 5-10).”

So, almost seven million tanoak trees cut down before 1907, which just happens to be when Calvin Stewart began bargaining for tanbark in the Mattole Valley. It is easy to see how a decade sending our bark either to the San Francisco, Santa Cruz, or Stockton-based tanneries, or to the Wagner refinery in Briceland, could take out most of the Mattole watershed’s supply.

According to quick internet searches, the most “efficient and effective” method of tanning, among many chemical choices, is to use Chromium (III) Sulfate. This technique (“chrome tanning”) has been known since at least 1840, but did not come into widespread use until around 1920, then became far and away the preferred process after the technological advances spurred by World War II. However, “vegetable” tanning continued to be used. It is a much less toxic process, and suited to treating leather for certain uses, mainly in furniture, footwear, belts, and other accessories, as it does not produce as flexible a leather as treatment by either the principle chemical or animal (brains, as used by Native Americans) means. Deer-brain-tanned deerskins, for instance, are wondrously soft.

Vegetable tannins occur in the bark and leaves of many plants; chestnut, regular (Quercus) oaks, and hemlock, as well as many tropical trees, have high tannin levels. These compounds bind to the collagen proteins in leathers, making them less water-soluble and more resistant to bacterial rot. (The largest tannery in the world in the 1840s was a hemlock-fed plant in upstate New York.) • ~LWC

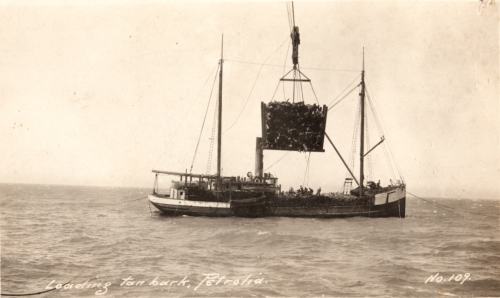

Another R.J. Baker shot of the Mattole Wharf. The wood planking and iron rail situation looks a bit busy and sketchy. Still, they managed to get those bundles onto the high lines and into the vessel.