This story was shared with me by Bob Stansberry, part of whose spread lies on the old Kreps place. I am printing it with the kind permission of Roy Forcier of Ferndale, the son of Myrtle Kreps Forcier. The accompanying photos came through the same channels. Notes in [brackets], subtitles, and captions are mine.

I am grateful to Bob and to Roy, and certainly to Judith Hokman, for making this story accessible. I will not comment on it, but let you enjoy it as is, other than to remark that the day Myrtle was born–August 30, 1913–was almost exactly a century ago. The Kreps family’s pioneer lifestyle, which was the only lifestyle that allowed one to enjoy the advantages of the fresh water and other pleasures of Wilder Ridge in the 1910s and ’20s, is described as something the earliest American settlers of a half-century before, and to some degree the back-to-the-landers of a half-century later, would recognize. John, Charles, and Sylvia Kreps were like latter-day pioneers in search of purity and the American dream, and were willing to work very hard for it. Let’s hear their story:

The Kreps of Kreps Ridge: A Family History

by Judith C. Hokman

John Kreps was born in 1850 in The Dalles, Oregon. [However, the writer’s own notes say he was born in Illinois; censuses say born in Ohio of Swiss parents.] He was thirty-two and an accomplished blacksmith when he married Minnie Laura Camron, eighteen. They had a son, Charles, born July 6, 1883, [and] two daughters, Ethel Ann and Mary Elizabeth. John and Minnie Laura led a nomadic life in Oregon and California searching for the perfect place to live and raise children. They moved from one rapidly growing community to another where John always found work in the blacksmithing trade. Sometimes they moved because the water in a community became impure, causing outbreaks of typhoid fever and hepatitis. The quality of the water became a very important factor in John and Minnie Laura’s search.

Traveling was hard on Minnie Laura, and she died of consumption in 1886 at the age of 24. [Research indicates her dates as 1864-1888; married to John Kreps September 3, 1882, in Wasco Co., Oregon.] Her two daughters were cared for by their grandmother and an aunt, and stayed occasionally with their father. John kept his son Charles with him as much as possible.

When Charles was twelve, John heard of the fresh pure water of Humboldt County and moved from Salinas to Rohnerville. Not long afterward, John, more fiddle-footed than ever, left his children with relatives and took a trip to the gold fields of Alaska. He did not find what he was looking for there, as returned to Humboldt and his family. He knew Humboldt had what he wanted, but felt that it was not in Rohnerville, where neighbors could get near enough to pollute his water.

Arrival in Mattole

In 1903, Charles Murphy showed John 160 acres of wilderness land he had acquired three years before at a tax sale. The land stood on the Mattole River near the trail which ran between Honeydew and the Garberville-Shelter Cove trail. A previous homesteader had cleared an area of nearly ten acres and planted fruit trees and built a small cabin. A year around spring with delicious soft pure water flowed down this gently sloped side of the jagged mountain. A quarter of a mile from the cabin was a plateau of 10 to 15 acres suitable for raising grain and hay. When the plateau was cleared, the meandering Mattole would be seen at the bottom of a 500-foot cliff.

John bought Murphy’s 160 acres in August, 1903, for $560.00, and decided to homestead another 160 acres adjoining to the south and west, on which he found several springs and a better southwestern exposure for a homesite. He was convinced that this and an additional purchase of land toward Fourmile Creek would enable him to bring his family, at least his son, near him. When his son should marry, there would be plenty of room for him to settle and raise his family.

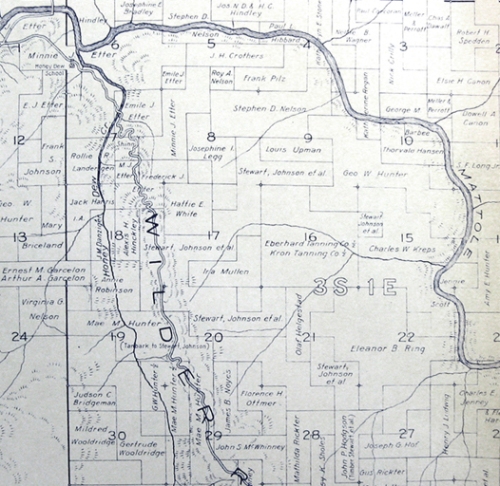

See Section 15, center right, for Kreps place on this 1921 map by Belcher.

There was demand for a blacksmith in the Mattole Valley, so John first built his forge and shop, then set about the task of building the house. It was built entirely of hand split redwood, except the living room floor which was fir planking. Redwood shakes covered the roof. At first the house contained only a living room, approximately 20’ x 20’, and two 10’ x 10’ bedrooms. A kitchen and pantry were added to one side of the building, their floor level three steps down from the rest of the house. There was a porch on the pantry end of the kitchen that held a water tank. Water was pumped from the spring by a water ram to the huge oak water tank. From there, the water was piped to the redwood kitchen sink, hand hewn by John. After the house was completed, he built fences and the barn, smoke house and other outbuildings. This was an impressive sight on the sloped hillside of the rugged mountain ridge. The buildings were all made of the same material and spaced to give adequate room for the purpose of each. The hand split fencing was whitewashed and made a nice frame for the seasoned redwood buildings.

Meanwhile, Charles had grown and was working for shingle mills in the Fieldbrook area. He worked mostly for Burns Shingle Mill at Camp #4, and helped his father at the homestead when he was out of work. Charles drove himself at any job he did. He was never idle. Whether gainfully employed or helping someone else, he worked hard and furiously.

The Hansen family’s eldest daughter

Sylvia Hansen was a very pretty girl with dark hair and eyes and delicate features. She was small boned and slender which made her look taller than her 5’ 3” height. Born in Wisconsin of Norwegian and German parents, Sylvia was the second of nine children, the oldest being her brother, Henry. Her family came to Humboldt from Elko, Nevada, where two younger brothers had died on a fever blamed on the water. They settled on a homestead site in the Bald Hills area [between Orick and Weitchpec] where after they had built a cabin and outbuildings, and cleared and planted fruit trees, they were told that they were on someone else’s land. The newly disclosed owner paid the Hansen’s $1,000.00 for their improvements on the land. The Hansen family moved to Trinidad, and there Sylvia met Charles Kreps at a young people’s dance.

Sylvia and her brother Henry were close friends as well as being close in age. Their mother occasionally worked as cook and dishwasher for nearby mills, leaving Sylvia to do the housework and care for the younger children. When he had no paying job, Henry helped her with the household chores. By the time she turned eighteen, Sylvia wanted very much to leave home to make a life for herself. It was very practical for her to accept the marriage proposal of Charles Kreps. He was a mature 28 years old, was of pleasant nature and worked hard. With her meager education and no training for such jobs as a woman was allowed to hold in 1912, plans for her future had to include marriage as the primary goal.

Charles and Sylvia were married June 1, 1912, and went to live at Camp #4, where some of the cabins were taken over, redecorated and made cozy by young married couples. Their first child, Myrtle May, was born August 30, 1913, in the old Trinity Hospital in Arcata. Three months later, the little family moved to the nearly completed homestead.

The weather in late November was foul. It took three days to get from Arcata to Petrolia, and almost as long from Petrolia to what had become known to them as Kreps Ridge. The horses mired down in the mud and had to be rested often. There was much concern for the tiny baby, who was wrapped in extra coats to insure her keeping warm.

Their largest possession to be moved from Camp #4 to the ranch at Kreps Ridge was a piano Charles had won in a raffle shortly before his marriage. The new piano had stood for some time in the dining hall at the camp and was slightly banged up around the edges. It could not be carried in a wagon to the homestead because the trail was rough and the combined heights of the wagon and piano made the load impossibly top heavy. A sled had to be built for it. The piano was then laid on its back on the sled which was pulled by two horses up the trail that ran along the tops of the ridges. It was a slow process, but the piano arrived at the house intact, if somewhat out of tune.

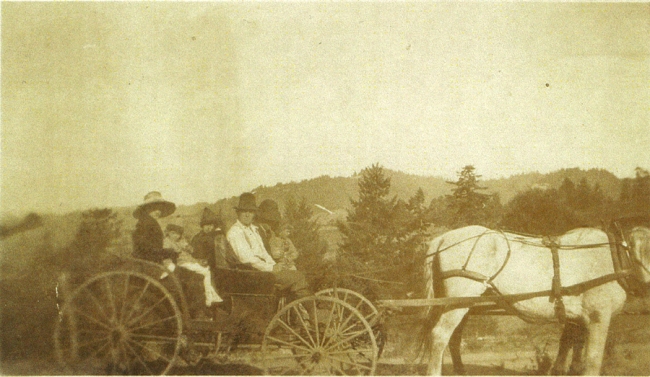

The young Kreps family– with grandpa John

John adored Sylvia from the first. The quiet-mannered, youthful girl reminded him of his lost Minnie Laura. He soon found out that Sylvia knew little about homestead life. He taught her how to make soap and patiently showed her how to can and dry fruits, salt pork, make jerky, and smoke fish and meat.

In the midst of all these lessons, Sylvia gave birth to her second daughter on October 11, 1914. Ethel was born in Petrolia at the house of Mrs. Booth [Mrs. Boots, most likely] who was a midwife. Following pioneer tradition, Mrs. Booth often exchanged her skilled services for produce from people with little money. She gave a much-needed service and without her help, there would have been a much higher mortality rate of both mothers and children in the Mattole Valley.

When World War I started in 1916, both Sylvia’s brothers Henry and Oscar went off to serve their country. She had never been so completely out of touch with Henry. Since she had been at the ranch, he and Oscar had come to visit when they were out of work. Having never been as close to anyone as to Henry, she could talk to no one of the fear she lived with that she might never see her beloved brother again. Her hands were busy with hard physical work, but her mind was uneasy.

She washed clothes on a washboard for three adults and two tiny babies, which was no easy job. The water had to be carried by the bucketful to the washtub, whether it was heated indoors or out. Clothes, heavy with water, had to be lugged from the wash to rinse tub, then wrung out by hand and slung over a line to dry. It took all day. She was interrupted frequently to feed and care for the babies and prepare meals for two hungry men. In order to ease life for the girl, her father-in-law bought her a treadle sewing machine and eventually a hand-operated washer with a clothes agitator and wringer.

Charles worked hard and expected everyone to do as much as he. When he ordered Sylvia to help with the butchering, John took over her part of the hated job and sent her and the children for a walk. He thought it enough that she have the job of preserving the meat. Though there were some jobs she detested, Sylvia was not lazy. In pioneer life, there is no room for shirkers. She worked hard in both the summer and winter vegetable gardens and grew some flowers of which she was very proud.

A welcome addition, and a sad loss

January 1916 came with little word of the war. Sylvia was ready to deliver her third child and there was 18 inches of snow outside the cabin. Her labor started. There was not enough time to struggle through the snow to Mrs. Boots’ in Petrolia. The best Charles could do was to go to Ettersburg for Mrs. Etter. Not long after he had gone, the baby came. John carefully and gently tended her while she gave birth to her son, Clyde Leland. It was a thrill for the old man to hold his only grandson in his arms. During her recovery, he let no one except himself care for the infant. This was what he had been waiting for. The land, this long-searched-for homestead would provide for his children and grandchildren.

John died suddenly of a heart attack on June 11, 1916 when his grandson was 5 months old. He was buried in a graveyard on the Roscoe place at Upper Mattole. How sorely his gentle nature and kindness were missed by Sylvia. She was separated from the two people she loved most.

Life, after John’s passing, was extremely lonely for the young mother. There was a period of more than a year that she did not leave the ranch. The only breaks in the monotony of chores and children were occasional travelers who saw the cabin from the trail on a nearby ridge and stopped over for a meal or shelter. Of course, Charles brought her stories about his trips to Petrolia for supplies and mail. The nearest woman with whom to visit lived three miles away over a steep trail. As the children got older and were better able to manage, the trip could be made as often as once a month in summer.

Henry and Oscar came home from the war in 1918. They had many stories to tell of places they had been and things they had seen. The several weeks they were with Sylvia and her family were spent hunting, fishing and telling of their adventures. The time flew by. Long after the boys had ended their visit, Charles and Sylvia, in their evenings by the firelight, sat and thought about the adventures the boys had had.

Sylvia and Charley with their children Ethel, Clyde, and Myrtle.

In the fall of 1920, Sylvia and Charles were raking hay in the grain field. There was an approaching storm that threatened rain, so they both were working at a hurried pace. Sylvia was leading the horse which was pulling the rake. She was deathly afraid of horses, but had learned to swallow her fear in the face of necessary work. The sound of thunder grew nearer. [Bob Stansberry notes that “During this time of year they were probably planting grain hay (oats) and raking the seed in with a spike tooth harrow.”] The horse grew skittish. At a loud clap of thunder, the horse shied and ran toward the trees. Sylvia kept hold of the reins and ran alongside of the horse until she tripped over a small stump and fell. The rake ran over her, the outside tine catching in the fleshy part of her side just below her ribs. The rake had missed her lung, but she had a terrible gash in her side that had to have the attention of a doctor.

Town trip, circa 1920

Charles had not been to Petrolia for their winter supplies of flour, sugar, coffee, tea, and spices, so decided to go to Eureka for those supplies as well as to get Sylvia to the doctor. He loaded the wagon with hay and grain for the horses and boxes of pears and other produce from the garden. Food, cooking utensils, blankets, clothes and other things needed for the three-day journey were added to the load. Sylvia struggled to prepare her family for the trip despite the wound in her side. They arose at 4:00 the next morning for their long ride.

It was the first time the children had been so far from home. They watched the stars go by as if they were a special show put on only for them. The first night’s camp was made at Bull Creek Flat and the awesome redwood forest was met before dawn the following day. At the second night’s camp near Scotia, a train passed by in the middle of the night and spooked the horses. Charles got up to calm them. The children were wild with excitement and were almost uncalmable themselves with so many new experiences in the middle of the night. Late afternoon of the third day, they could see Eureka.

A horse-drawn wagon with a canvas cover, carrying a pioneer family was a rare sight in Eureka in 1920. Automobiles had already taken over the majority of the roadways. Children and dogs chased behind the strange looking wagon, but older folks, their eyes full of nostalgia, watched as it traveled the streets of Eureka to Sylvia’s parents’ Eureka home.

Team and surrey was the family transportation before 1921 when the family purchased their first car, a Model T Ford. Sylvia, Ethel, and Myrtle are in the backseat; Charles, Clyde, and unknown passenger in the front [per Bob Stansberry].

Nearly seven years had passed since Sylvia had seen her parents and their younger children. She divided her time between listening to her mother’s reports on the family’s activities during their separation, introducing her own young family, and visiting the doctor’s clinic.

The trip lasted over a week, then the trip home began. Supplies were packed in the wagon where produce had been before. Fresh hay and grain were loaded. Clothes, camping equipment and children were made ready for the long trek.

Hours from Eureka it started to rain, pouring day and night. Small slides that had to be cleared in order to pass caused them to take an extra day to get as far as Pullen’s Elbow. There they had to stop to clear away a huge slide. The slide took nearly two weeks to clear. During that time, Sylvia and the children stayed in a cabin owned by Charles Davalt. The kind bachelor moved into his barn to make way for the family. Clyde, nearly five at the time, was fascinated by the fact that chestnuts covered the entire floor of one room of the cabin.

Home was reached over a month after it was left. The animals had been turned out to fend for themselves and had to be gathered up and brought home. Supplies had to be dried out and put away. Then life settled down for the winter.

Between house and woodshed on Wilder Ridge place. Charley and Sylvia holding horses with results of the hunt in the saddles. Myrtle said that they would hire out with their horses for work on the county road, at times [per Bob S.].

In November, Henry was out of work. He and his brother Chester, then a clumsy teenager, went to the ranch to visit and hunt. Sylvia was always glad to see her favorite brother even though extra work came with him.

Fate’s cruelty

One morning shortly after they arrived, Henry and Chester went on a bird hunting trip toward Upper Mattole. They crossed a new bridge being constructed near the old Way summer home. As Chester followed Henry across the wet slippery boards that rainy morning, he tripped and knocked the gun against a projection on the bridge which released the safety catch. The gun discharged and Henry took the full load of shot in the small of his back. Chester pulled him off the bridge and laid him in the road bed. Then he ran for help.

Henry was so badly wounded that only a doctor could save him. Stan Roscoe had a Studebaker Special with high clearance between the frame and the ground. It was the only car in the valley that could possibly make the trip over the deep muddy roads to Eureka. There was room in the back of Stan’s car for a cot to be made for Henry to lie on. A trained nurse who lived in the valley had morphine and administered it to him to ease his pain. At what seemed to be hours later, the car was ready to go to Eureka.

Between Upper Mattole and Honeydew, the car bogged down several times. Near the Honeydew bridge, stuck again, the cause seemed hopeless. Chester and the three other men making the trip with Henry frantically dug the car out again, then went to check on Henry. He was dead. He died with no last words, under the big oak tree on Hadley Flat [this should probably read “Hindley Flat”].

They took Henry to the Hindley Ranch to await the coroner. After the coroner came, he was taken to his family in Eureka who buried him in Ocean View cemetery. Chester went alone to tell Sylvia of her brother’s death, a most pathetic boy who would carry a great burden with him ever afterward.

Sylvia did not attend Henry’s funeral. Winter was coming on and Charles thought it unnecessary for her to go to Eureka. She could do nothing for Henry. She grieved alone in the cabin on the ridge.

Expanding horizons

That winter, Clyde turned six. Since there was no school near enough for his children to attend, Charles had to move his family to a place nearer a school. In the spring of 1921, he purchased 15 acres on the east bank of a bow in the Mattole River just west of Honeydew. The Kreps family moved to the site and lived in a tent while Charles built a cabin with the help of some of the men in the valley.

Three redwood logs used as a foundation for the cabin gave a feeling of solidity except during earthquakes when they would roll, causing the cabin to pitch violently back and forth. The children had been dreadfully afraid of earthquakes all their lives, having had quite a number of them at the ranch. When they were small, their Uncle Henry used to scare them with a tale of the 1906 earthquake in Bald Hills. He said that the trees leaned over so far they almost touched the ground. An earthquake in the rocking house was a far worse experience for the timid children.

Clyde remembers an earthquake that came in the middle of one night after he and his sisters, all with colds, had had their chests plastered with rendered skunk grease, given a homemade cough remedy and sent to bed. Uncle Willie was staying with them. The earthquake hit. It dumped Uncle Willie and his bed over, whipped things out of cupboards onto the floor and threw the sourdough and all the medicines into a giant mess all over the kitchen. Clyde was sleeping in a cot by the piano. With each tilt of the floor, the piano bashed his cot, moving it halfway across the room. In the midst of the chaos, the house gave a lurch, the door flew open, and the shotgun fell out, the stock leaning against the outside wall. The house lunged back again and shoved the gun’s barrel into the ground. Although he was scared out of his wits, Clyde’s fear was overcome by relief that all those old medicines were ruined.

School days

The cabin, which was almost exactly halfway between Honeydew and Upper Mattole schools, was in the Upper Mattole School district. The children walked three miles to Upper Mattole school until the road slid out making it dangerous for them to pass. From then on, they walked three miles to the Honeydew school. Spring, summer and fall were the months school was in session, leaving the winter with its bad weather for vacation time.

After adjusting to being with children other than themselves, school in the one-room schoolhouse was fun for the Kreps children. Clyde, young, inexperienced, and gullible, took the longest to adjust. He thought school an unnecessary evil that kept him penned up inside and he wanted out. Believing everything anyone told him, he was more than happy to help the older boys when they said they knew of a way to close down the school forever. He filled a tobacco can full of skunks’ stink bags and one afternoon smeared them all over the schoolhouse. Caught by the teacher, who could smell him a mile away, he was made to clean the stink off the building. She was very angry with the boy and threatened him with reform school. This made a believer out of him, and all trouble he was a part of after that was minor. He didn’t realize for years, though, how she had known he was the culprit.

Charles divided his time between the place on the ridge and the 10-acre garden he and Sylvia had made on the river. Wherever he worked, his family went with him and worked right along beside him. One would have thought they were all men, the way he worked them.

Seven-year-old man

When Clyde was between seven and eight years old, Charles decided to take him on a sheep drive to the railroad at South Fork. Sylvia argued that the boy was too young, but Charles could not be dissuaded. He must learn the ways of men sometime, and there would never be a better time.

The Lindley, Etter, Shinn, Roscoe, Hindley and Kreps families put their sheep together for the drive. There were more than 3,000 sheep to drive to the railroad. Each family packed a roll of fencing which when connected together, corralled the sheep at night. They also packed provisions and camping supplies for the three-day drive to South Fork. The sheep were all brought to Honeydew where the drive began.

The destination of the first day was Nigger Heaven, where the sheep were weighed. Halfway through the weighing, it started to rain. The job was hurriedly finished, as they buyer didn’t want to pay for water retained in the wool.

The second day the sheep were driven to Bull Creek Flat, rounded up and corralled for the night. People who lived in the Bull Creek area came to visit the camp that night to trade news and gossip. Guy Curless and one of his sons were among the visitors. The son, while wandering around in the dark, stepped ker-splatt into the frying pan. This was one of the high points of the trip for seven-year-old Clyde.

By dark the third day of the drive, the sheep were loaded in the railroad cars. The job finished, the tired herders ate supper in a diner made from a railroad car. They were relieved that the successful drive was over. The camaraderie of the men in the diner was loud and jovial, making a comfortable happy feeling for the exhausted little boy.

The next day brought them home. Sylvia became anxious for her son as he slept the clock around, talking in his sleep the whole time. On his waking, she and the girls enjoyed the vivid account of his trip.

A boy and his dream

When he was 11, Clyde wanted a bicycle. Since he had been trapping animals for quite some time, his father told him he could trap and sell pelts, using the money to buy a bike. The one in the Montgomery Ward catalog cost $39.00 plus shipping. It seemed like an impossible amount, but Clyde was determined to have his bicycle.

With the company of his dog, Mush Hound, he spent the winter trapping. Skunk pelts brought $1.50, and raccoons, $2.50. A mink hide, which Mush Hound assisted in catching, sold for $10.00.

Of course, one could not work all the time. When trapping was slow, Clyde used to tease Mush Hound. The dog loved to eat hard Christmas candy. He would stand and chew and chew and chew until he had finished the candy. Clyde piled a few pieces of candy in the middle of the trail and while Mush Hound slowly ate them, he ran as fast as he could up the trail, then stopped, doubled back on his tracks for a way, and jumped off into the brush where he could watch the dog.

Mush Hound finished the candy and raced along the trail Clyde had taken. When he came to the end of Clyde’s tracks, he nosed around trying to find the boy. After several moments, Mush Hound doubled back along the trail and finally found his friend. Both boy and dog delighted in this game and it was played over and over.

Clyde used to take a .22 caliber rifle with him when he checked his trap lines. One winter day, darkness overtook him long before he reached home. Since he did not trust the dark, he saw things and heard noises all around him. As he rounded a bend in the trail, he saw the unblinking green eyes of a panther staring straight at him. He stopped dead in his tracks and with his heart beating wildly, raised his gun to his shoulder. he shot. he saw feathers everywhere. His dangerous panther had turned out to be a harmless old owl.

He had one other mishap with a bird. He caught a large grey heron in one of his traps. Its leg was not hurt, but it was held fast by the trap. He did not want this bird and approached the trap to set it free. The great wings of the huge bird flailed away at him. When the heron was free, it flew away with no thanks to the bruised and battered boy on the ground.

By the end of the winter, Clyde had earned $80.00 and the bike was on its way. By coincidence, he and his father were at the Honeydew store when the bike came down the hill aboard the Albee Stage. The boy waited excitedly as John Albee untied the carton from the side of the big Dodge truck. Clyde and his father took the bike right home and put it together. He was proud to ride his new bicycle the three miles to school. He worried, though, for the safety of this prized possession when he was naughty at school and had to stay in at recess. the other children would play with his bike, while he sat fidgeting at his desk, hoping they would leave it in one piece.

Farewell to all that

In 1929, the Kreps family was forced to move again. It was time for high school for Myrtle and Ethel and junior high for Clyde. Charles was determined that his children would have a better education than he, so moved his family to Eureka.

The children, old as they were, were beings of the forest. City noises and the great numbers of people encountered there, confused and frightened them. Sylvia saw how terrified they were. She remembered her search in the woods for three very small children who had run away from the cabin on the ridge. Uncle Willis had told them he would cut off their ears if they were naughty. But that was many years ago. This was 1929. They would adjust. She had known the loneliness of life out there and would never go back.

A short while ago, Clyde’s grandchildren visited the ranch at Kreps Ridge. The original house and outbuildings had burned down years ago and had been replaced by a summer cabin. Though the trees are old, Murphy’s orchard and the orchard on the homestead still bear fruit. There is no electricity or telephone there, and the springs still run sweet and clear. The solitude and quiet of 1903 still prevail.

*Notes from writer Judith C. Hokman, from 1976: “This account was written with love of history and even more love for some of the people in it. Thank you all who helped me so unselfishly. Special thanks to: Mrs. Elizabeth (Toots) Clark, Mrs. Myrtle Forcier, Mrs. Ethel Armstrong, and Mrs. Martha Roscoe [all of Eureka]. Very special thanks to Clyde Kreps of Bridgeville, whom I love and for whom this story was written.”