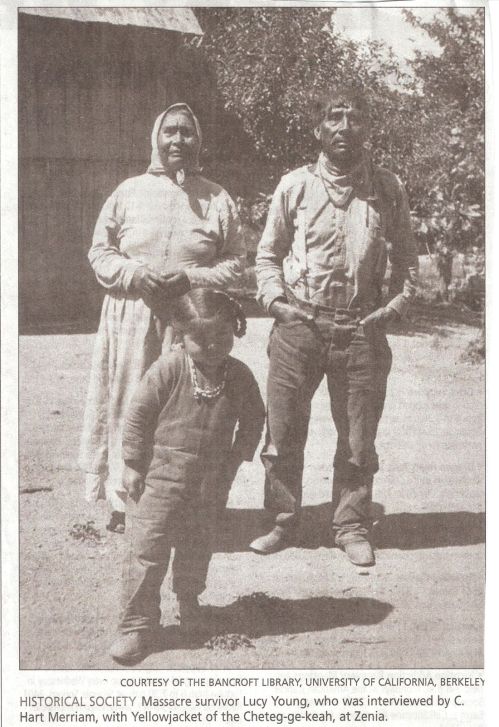

Here are a couple of pictures from the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley that i found online.

(As always, click on the photo to expand it; then do whatever your computer does to zoom in further.)

Joe Duncan, who learned his language before the first white person was seen in the Mattole Valley. Born perhaps c. 1850, he was informant to anthropologists here in the 1920s. His Indian name was something like "Taralash".

.

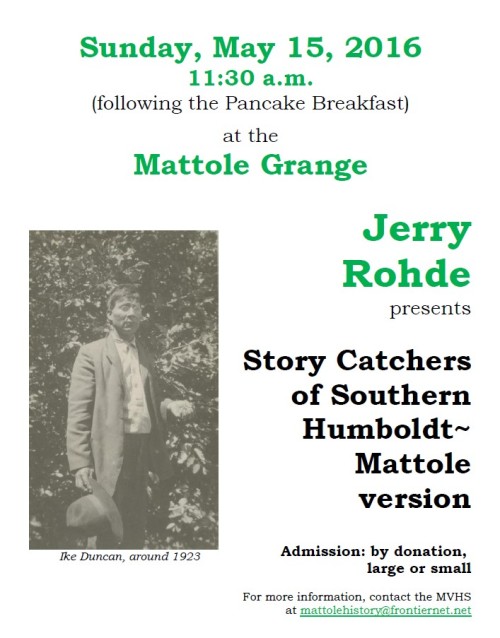

Both these pictures are of Isaac (also called Ike) Duncan, Joe’s son. I recently learned that Leonard Bowman, chair of the Bear River Band (Rohnerville rancheria) is Ike’s descendant. 1923 photo.

.

Ike and Joe Duncan were a couple of those Natives left living near the mouth of the river after the official Indian Wars were over. They hired out as ranch hands, and seemed to be generally well-liked and well-respected. In 1927, a linguist famous for his work with Tibetan as well as Native American languages spoke with the Duncans; i have had a few clues leading me to the conclusion that it was Joe and Ike, rather than, say, the Denmans he spoke with. I found online an interview with Dr. Fang-Keui Li from the 1970s about his visit to the Mattole and his experiences with the Duncans:

Li:

After a few weeks he [his mentor and boss] said, “Well, now you can go. You know all the techniques of how to ask questions, how to handle your informant. Now you can go and try to look for the Mattole Indians.”

The Mattole Indians were known to be along the Mattole River, but they were supposed to be extinct. That is to say, all the Mattole Indians had died. But there was news that there were still one or two still alive. One of our projects was to make a record of all those Indians that were still alive, because after that, that language would be dead; it would be no more. As a matter of fact, that is the case.

I took the material of the Mattole Indians after I got to that place and did about four or five weeks of recording texts and grammar and so on. After I left, I know that all the Indians of that tribe died [this is not quite true; however, Native speakers of the tongue were probably hard to find by the 1920s], so my record of that language is still the only record of the language.

After I left Hoopa Valley I went to some place called Fortuna, in order to look for the Mattole. So I wandered around all over that area in a taxi, asking where the Mattole Indians were. It was a kind of wild goose hunt.

But some people said, “Well, further south along the Mattole River you may find some Mattole Indians.” There was no bus or anything but a kind of a so-called post truck, that sent letters from one village to the other. So I took one of those trucks and went down to a small town called Petrolia. It was called Petrolia because it was thought at one time that there would be oil in that area, so that little town was called Petrolia.

I stayed in a hotel and started asking whether there were Mattole Indians there or not. They said, “Well, yes there are Mattole Indians, but they are on the mouth of the Mattole River on the Pacific Ocean. There is one family we know there who are Mattole Indians.” It was about, oh, three or four miles from Petrolia.

The only thing to do for me was to take a walk to the mouth of the river, and so I started walking. There was just the Mattole River going one way, so I forded it one way, and forded back and forth the other way, until I came to a farm house. I found it too hard to walk further (some 10 miles), so I borrowed a horse from a farmer. I said, “Can you lend me your horse so I can ride it to the mouth of the river?” The farmer was very nice, he said, “Yes, you can take my horse.” He started to put on the saddle, you know, for me, and I said, “I want a very old, very good-tempered horse, because I never learned how to ride.”

He said, “Oh, this is an old horse.” He said, “Now you take this, and if you follow the river, you’ll go down and get to the place. When you come back, take the horse to the stable.” He didn’t want to have any money paid.

So now the first time I took a trip on that horse, and went down to the mouth of the river and met these two old Indians. One was very old, seventy something, the other was about forty, fifty, something like that. I started asking them questions about their language.

The old man, I think was blind or something.

I asked them, “Will you teach me how to speak the Mattole language?” He apparently was willing. I said, “It is impossible for me to make a trip every day to your house. You have a horse.

You can ride down to town every morning, and I will provide you with a lunch at the hotel, and after we work, about four o’clock, you can ride back, and I’ll pay you for your trouble.”

At that time I inquired of Kroeber what was the normal rate to pay an informant. This is important, because you have to know the local rate in order not to pay more than the University of California, you see. Because that would have spoiled their game. Kroeber said, “Oh, pay him about forty cents an hour.” Forty cents an hour, for one day of six hours. “You pay him two dollars something, and you give him a lunch.” At that time that was quite sufficient; forty cents an hour was the going rate for the University of California.

So I told him, “I am going to pay you forty cents an hour,” and he was happy because he wouldn’t be able to get anything, normally. So he came every day to me, and I got some material for a little bit over a month.

I found him very dull, a very dull person. He didn’t know how to get your point, what you asked. And he could not–I said, “Can you tell me a story?” I thought I would give him–. No, he didn’t know how to tell story. [all laugh] It is a difficult thing. You do get informants that cannot tell stories. If you ask you, yourself: “Can I tell me a story?” You’ll search, but you may not be able to find any story to tell.

So he could not tell a story.

Peter:

This was the younger person?

Li:

Yes, the old man could not come out; he was blind and over seventy years old. He could not come to me.

Lindy [Li’s daughter]:

He probably knew the stories.

Li:

I got mostly grammatical material, like “I come, you come, he comes,” and so on. This kind of grammatical material which you could easily get from him. Or, say, “I go from here to there,” and so on.

So, after a little over a month I found that this was getting a little bit–the, how would you say it? Economically it is called what, the limit of returns?

Lindy:

Diminishing returns.

Li:

You stay longer, you get less. So I said, “I had better try another Indian tribe.”

~ [Can’t seem to post an active link here, so just Google “Linguistics east and west: American Indian”, type “Mattole” into the Search box, and you will find lots more good stuff where this came from.]

John Jackson, a.k.a. Johnny Jack, at his cabin at the mouth of the Mattole. He had a daughter named Cora (Greslik, then married to an Everett Anderson) who was around here up until the 60s, at least. This photo from the Mary Rackliff Etter collection.

The Merrifield family of the Phillipsville/Miranda area, c. 1915; courtesy of the HSU Library, Humboldt Room

Truman Merrifield, or Mayfield as the name is sometimes spelled, was the son of Daniel Merrifield, a white man originally from Vermont, who got together with a Native Mattole woman in the 1860s. There was a daughter (Rhoda?– let me correct this later when i’ve looked that up), and son Truman, who married another Native or half-Native woman– here is their large family.

Read Full Post »