Today’s post is part of my slowly ongoing effort to republish, online and available for researchers’ use, articles from our Mattole Valley Historical Society archives that may be of interest to distant historians, students, and aficionados of all things Mattole. This lengthy entry is a slightly edited version of the article called “Oil Dream Creates Petrolia in Lower Mattole,” from the Now… and Then newsletter of Summer, 2004 (Vol. 6, n.1). It omits the original introduction regarding the first Euro-American settlers of the area, beginning instead with their first awareness of the petroleum deposits beneath their feet, and their hopes for the commercial potential therein.

~~~~~~~~

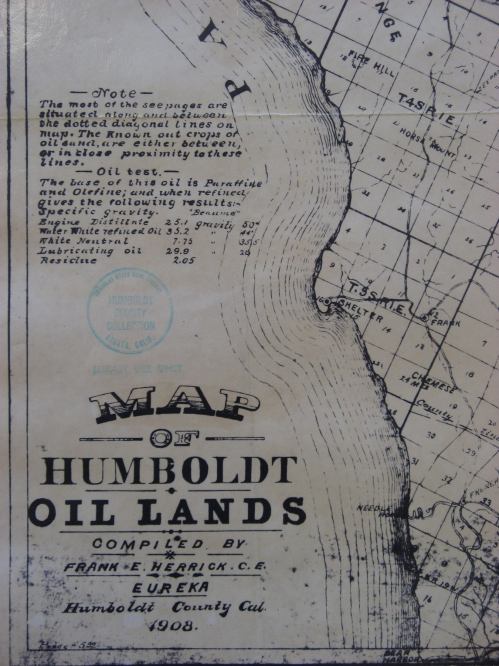

An oil well, location unknown, in the Mattole Valley.

From the Mary Rackliff Etter collection.

Oil seeps into the picture

The discovery and export of oil and related products changed more than the location of Lower Mattole’s business and population center; it is difficult to overstate the impact of its promise on the course of history here. If you can believe that the proposed name for the town was Petroleum, that there was a settlement in the Valley known as Oil City, and that the legal name for the U.S. Post Office at Bear River was Gas Jet, you can perhaps imagine the future those oil enthusiasts would have provided for us if they could have.

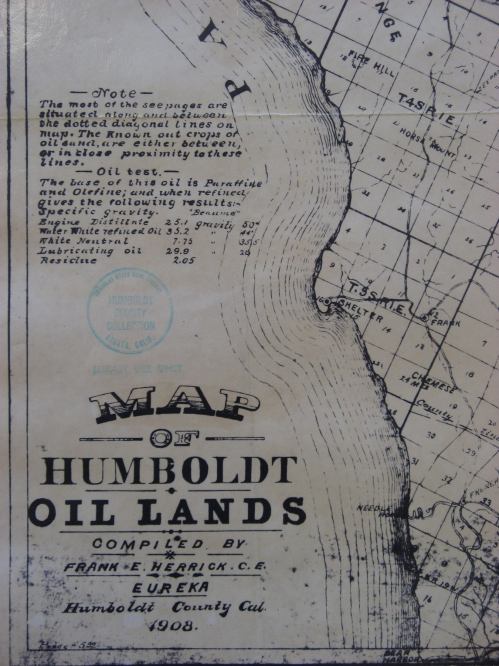

The first mention of oil deposits in the local newspapers was made in 1859, when the Humboldt Times announced that petroleum springs, seeping “rock oil,” had been found both at Bear River and five miles down the coast from Cape Mendocino. (Credit must be given to Owen C. Coy for his history, The Humboldt Bay Region, 1850-1875. I am basing much of this general information about the oil boom on his research. When I credit HT, I am referring to the Humboldt Times. This first reference to petroleum in the area is from HT, June 25 and Nov. 19, 1859.)

To the wider world, the exciting news was given on February 1, 1861, in The Sonoma Journal and Mining Press. According to Coy, outside interests then invested $10,000 for the right to drill on the property of J.A. Davis near Cape Mendocino. Their efforts must not have been fruitful, for there is little more mention of oil until the Mattole Mining District was formed in November of 1864. The District drew up boundaries for a jurisdiction in which members’ rules would apply; the rules are ten articles regulating staking of claims (one-quarter section, or 160 acres, in a square body, to be posted then registered in the Recorder’s Office with boundaries described, within 20 days of claiming; landowners’ fruit trees or other agricultural improvements should not be destroyed, etc.). Other Districts were formed rapidly thereafter, following much the same guidelines. Soon the entire Valley, and indeed, much of Humboldt County, was included in Mining District descriptions.

In the order they are found mentioned in a chronological scanning of the Times for 1865, and also in Coy’s book and other sources described below, the Mattole-area Districts were:

–Mattole Mining District

–Walker District

–Pennsylvania ” ”

–Upper Mattole ” ”

–Shelter Cove ” ”

–Mendocino ” ”

–Bear River ” ”

Now, these Districts were more like self-protecting and self-regulating associations, rather than actual business enterprises. The first of the successful operators was the Union Mattole Co., incorporated in March, 1865; it owned a square mile where its most successful well was drilled in Sections 30 and 31 of T1S, R1W, about four miles southeast of the Joel Flat enterprise. Another, incorporated in May of 1865, was the Jeffrey Company. The Oil Creek Petroleum Company is noted in July, as are the Stansberry Petroleum Mining Co. and the Grissim and Walker Petroleum Co.; the Main Mattole River Petroleum Company was incorporated in August; and the Mattole Valley Oil Mining Co. also in August of 1865.

The wells themselves were as often mentioned as the corporations who owned them. McNutt’s Oil Spring, which is either the same as or very close to the Sutter and Allen Well on the McNutt Claim, the Union Mattole Well, the Mattole Petroleum Company Well (northwest about two miles from the Union Mattole Well, and approaching Joel Flat); the Joel Flat or Henderson Well, the Erwin Davis Well, the Jeffrey Well, the Betts’ Farm Oil Well at Upper Mattole, the Hawley Farm Well, and the Cassin Farm Well all operated here in the Mattole watershed; several were moderately, that is, promisingly productive, and many were bored to a depth of over 400 feet.

1865 and J.W. Henderson

1865 was the year of spectacular hopes for oil wealth. The Mattole Valley Historical Society has recently been very lucky to obtain, in a wonderfully timely manner, surprise donations of documents key to that year’s affairs. First, Ferndale Books called with the offer of nine folders of original documents of incorporation for Mattole-area road companies and oil mining outfits. We are extremely grateful to Jere Bob Bowden, who called the papers and their relevance to the M.V.H.S.’s concerns to the attention to the Benemanns, and to Marilyn and Carlos Benemann, who gave them to our Society. Then, out of the blue, we got an e-mail from the great-great-grandson of James W. Henderson, offering us copies of his ancestor’s daily journal–beginning in the year 1865! We shall see the great interest and value of these records as our tale progresses; but it’s fair to say that our little town could just as well have been called “Henderson Center,” as was J.W. Henderson’s well-known neighborhood development endeavor in Eureka.

A few hours of research into the Humboldt Times for that year, and many days at the Humboldt County Recorder’s Office, and now I believe we probably know enough about 1865 in the Mattole Valley to keep us happy for a little while.

Henderson’s journal is mainly a record of business transactions and travel; he rarely expresses an impractical thought. He was, according to Irvine’s 1915 History of Humboldt County, born in upstate New York in 1828. His father was of Scottish parentage, his mother born in Wales; both parents were devout Episcopalians. In 1849 James W. Henderson headed west, arriving at the gold fields effectively broke; but soon he had his starter chunk of gold, and discovered his knack for all manner of business–buying and selling of merchandise, horses, mules, etc. He carried the U.S. mail between San Francisco and Weaverville for several years, and in exploring northern California found Humboldt County agreeable. He pursued his Petrolia dream in 1865 while in the process of moving his family and household from Petaluma to Eureka.

Henderson was certainly a sharp trader; he at one time held upwards of 15,000 acres in Humboldt County. Yet he was not only a man well-respected for his wealth; he was admired for his public spirit. He gave back to the people, and his business endeavors were performed in the hope that his profit would be the community’s gain as well.

James W. Henderson’s journal entries may at first seem a little dry, but with careful inspection much can be gleaned. The prices quoted should be multiplied by twenty to thirty, except for land prices, which we can only wish were anything close to twenty times what he paid; and wages, which likewise are now inflated disproportionately to the twenty-thirty times increase in the price of, say, a bottle of whiskey for seventy-five cents, or overnight hotel stay for two or three dollars.

For instance, on January 1, Henderson writes, “Got an early start and expected to go to Mattole. Could not pass Salt River. Paid Hotel Bill–$2.50. Ferriage–$1.25. Grain & feed–$2.50. Stopped all night on the Island!” And on the next day, he relates, “Came to Mattole. Arrived after dark.”

Perhaps some of you don’t know Salt River. There’s still a sign for it as you drive toward Fernbridge from Ferndale; it’s a branch of the Eel, once navigable all the way up to Port Kenyon, that came so close back around to the main fork of the Eel (east of the present road) that the land between the watercourses was virtually an island. So Mr. Henderson had difficulties we would not likely experience today, what with ferrying across the Eel and being stranded on the Island; but still, making it all the way to Mattole the next day is not too shabby. Evidently horseback was the way to travel this country. In a later–September, 1867–entry, Henderson is working on the new road to the Cape Mendocino lighthouse, as well as assisting with the salvage of the Shubrick, down the coast below King’s Peak. He writes on Friday, “At the Cape [Mendocino] hauling… At 4 p.m. started for the wreck of Shurbrick and come to Petrolia where I spent the night. Went to (Justice) Conklin’s to make affidavit…” and by the next day, Saturday, “came to the wreck at 11:30 a.m.” I don’t think I could get around any faster today.

The business of oil

Henderson had some money and his business was putting that money to work. However, he didn’t take it too easy himself; he seemed quite driven by his mission. He worked with, and seemed to defer on business judgment calls to, a man named Parsons, who gets a street in Petrolia named for him. Variously an L. Parsons, a Sam Parsons, and a Dave Parsons appear in my computer-typed transcript; later research revealed this man to be Levi Parsons. Leigh Irvine’s book states that Thomas Scott, the Pennsylvania capitalist, sent Henderson $75,000 to invest in Humboldt County’s oil lands. “Scott and Parsons Lease” is applied to several squares of the 1865 map in this area; it looks like Parsons was a sort of middleman between Thomas Scott and James Henderson. Reading the journal shows you men busy scouting out and procuring oil-bearing lands here, and generally making investments in the area that would be boosted in value by oil production. A railroad manager and tycoon named George Noble was involved in Henderson’s business as well, but the player I would like to know more about is the man behind the initials RHB on Doolittle’s 1865 map of Humboldt County. The Mattole and Bear River valleys are covered with squares bearing that designation, sometimes as “RHB Lease,” or “RHB L.” Nobody seemed to know what person or company the letters referenced; but J.W. Henderson mentions dealing with him several times, and in the Recorder’s Office, I found a slew of deeds to Rice H. Bartlett from various Mattole landowners. The papers granted RHB oil rights, usually for 1/4 section or 1/2 section pieces (160 or 320 acres), for anything from $2 to $5. I found over a dozen from the year 1865, for the lands of James Jeffery, Dennis McAuliffe, George Hill, Peter Mussen, Charles W. Gillette, L.W. Gillette–you get the picture; go over the map or the census and you will find the same names you find on these deeds giving RHB the right to explore for oil.

What was in it for the landowner? Five percent of the oil and /or the profits from the oil, if it was found. This 95%-5% split was almost universal. Once in a while a sharp trader would add or take away a provision; Peter Mussen makes a stipulation that boring must commence within 90 days of February 1, 1860, and that if oil is struck in paying quantities, $1000 in gold coin must be paid to the Grantor immediately. And while most of the deeds give RHB the right to take and use such wood and timber from the property as is necessary to make improvements enabling oil extraction, several people expressly withhold the wood rights. A few also exempt the few acres surrounding their homes from oil exploration.

So while I still haven’t gotten around to finding what big money backed Rice Bartlett, we can see what he was up to. The language in each of the deeds is almost identical; the Recorder’s job must have been quite tedious that year. It specifies that Bartlett is purchasing rights to “All the oil and all the Petroleum, Naptha, Asphaltum, and other substances containing or producing oil, by whatever name they may properly be designated upon the tract of land…”; then the particular sections are given their legal surveyors’ descriptions. Also, there are “provisions for roads, railroads, wharves, landings, wells, tunnels, shafts, workshops, houses, buildings, machinery…” etc.

The 5% return to be given to the landowner will be minus the cost of processing, “if desired by the Grantee, and other charges incurred after extraction from the body of the earth.”

Here is one way R.H. Bartlett turned a profit: On January 30, 1865, he purchased oil rights to 240 acres in Section 16, T2S, R2W (for your information, the land to the south of Lighthouse Road from the far end of the Triple R field to Mill Creek, and back up 1/4 to 1/2 mile) from George Hill for $5. On February 21, just three weeks later, he sold it to Erwin Davis for one hundred times that amount–for $500! We might want to feel sorry for Mr. Erwin, especially if we thought that was all his personal savings, though I doubt that; his backers must have gotten wind of a successful operation and felt very optimistic. The deeds show that every one of the leases purchased by Rice Bartlett in late January and February of 1865 was resold to Davis for $500 each! And as far as we know, of course, he (or his supporters) never got back a penny of it.

Roughly the same was going on in Upper Mattole. Tip Smith sold oil rights (or land; the rights were at least as valuable as the land) in the Frazier Mining District for $100 to G.H. Brown and A.G. Lafferty in September of 1865; in March of 1866, Brown and Lafferty resold it to the Mendocino Oil Company for $350.

But Rice H. Bartlett did have a heart; on March 15, 1865, he deeded to Mandana H. Bartlett 1/3 of all he’s worth, including his oil rights, just because of his “natural love and affection for his wife.” Oddly enough, that’s the very day James W. Henderson “laid off the town of Petrolia on the Stansberry Ranch.” Early in the year, James W. Henderson had made his big purchases–1200 acres, more or less–of lower Valley land in preparation for his new town.

The birth of Petrolia

Francis Stansberry owned a lot of land around the junction of the North Fork and mainstem of the Mattole. On January 3, 1865, Henderson writes, “Closed up contract with Stansberry for Ranch. Paid him $2000 coin. Closed with Hunter, keeps 1/2 L. and I pay him $250 for outside land.” The language of the Stansberry deed is for land “bounded on the south by the Mattole River, and the ranch of L.W. Gillette and brothers, on the east by the ranch of Miner K. Langdon, and on the north by the ranch of John Fruit, and on the west by the North Fork of the Mattole River, containing 600 acres of land more or less.” This is basically the square mile of flat land that was destined to hold in its center the platted town of Petrolia.

On the same day, the Recorder wrote of land purchased by J.W. Henderson from Walker S. Hunter, that the land was “bordered on the west by the ranch of Charles Cook, on the South by a creek [now McNutt] running from the ranch known as the Table Ranch to the Pacific Ocean, on the East by the ranches of B. Smith and A. Langdon, and on the north by the large hill north of the Ferguson House, containing 600 acres of land, more or less. But [Hunter] reserves 160 acres of land upon which his dwelling house now stands and in which he lives, and bounded on the south boundary of the land above described…”

On Monday, March 6th, Henderson went to Eureka to get John Murray, County Surveyor, to help establish the new town. On Saturday, the 11th, they “went to Stansberrys and then to Conklins, got our surveying party sworn in. Paid Conklin $2.25 for services in coming to Cooks’ [Charles S. Cook’s, which seemed to function as an inn or meeting place throughout Henderson’s journal].” By Tuesday, the 14th of March, he is “At Stansberry’s, made an arrangement with him to lay off a town on the land he has rented of me.” The old map we can still review from the mid-1800’s is dated March 15, 1865.

The Humboldt Times was not missing the news. On March 25, a short article notes that “A new town has been laid off in the coal oil regions in the lower part of our county, and lots therein find a market as readily as hot buckwheat cakes in winter. The town site was surveyed and laid off into lots and blocks by our County Surveyor, J.S. Murray, Esq., and located upon a portion of the place known as the Kellogg farm in Lower Mattole, which was between what’s now the Petrolia Square and the lower North Fork crossing. We understand that all the lumber on hand at the mill in the valley is secured, and orders for any amount more remain to be filled. The name by which the town is to be known has not been fully determined upon; Petroleum, Petrolia, and Mattole are suggested. One of the two former will probably win.” Happily, Henderson’s idea as he stated it on March 15 prevailed.

Media hype

The March 25, 1865, the HT features a very lengthy article titled “The Oil Region of Humboldt County, California.” An excerpt celebrates the Mattole’s possibilities: “Mattole country is particularly noted for the great number, and great activity, of some of its oil springs. We will not attempt at this time to enumerate them, or speak of their capacity, but will allude to one only, which is located, if we mistake not, on what is known as the Joel Rush flat or claim on the north fork of Mattole river. This spring, we heard it stated by those residing in the immediate neighborhood, discharges not less than one gallon of oil per hour. Of course this is an exception, yet there are many others from which no inconsiderable quantity of oil flows, and hundreds that discover its presence. This oil as it is taken from the springs, is used by the settlers in Mattole valley for illuminating purposes and can be and is burnt in the ordinary coal oil lamps without emitting any unusual odor. A prominent citizen of this place only a few days since tested a sample of the crude article by burning it in the ordinary lamp by the side of the rectified [oil], and his testimony is that there was scarcely a perceptible difference in the freedom with which it burned and the light it gave compared with the latter. It is undeniable then that Humboldt county possesses its oil region and that it bids fair to develop a source of wealth to its citizens, and such as shall make a name for itself and add increased lustre to the State of which it is a part… ”

We could go on–the Humboldt Times certainly didn’t stop in its promotion of the area as the potential oil capital of the world. On April 8, 1865, editor J.E. Wyman (incidentally, one of the Trustees of the Main Mattole River Petroleum Co., among other oil companies) enthuses, “The oil region of our country is daily attracting more attention and drawing thither a larger and more eager crowd. Additional oil and gas springs are being discovered and the range of country indicating the presence of oil is becoming more extended. Lands are being constantly and continuously secured in every manner by which it is possible to hold them free from interference. Some of the companies have secured many thousand acres…The region… is sufficiently extensive to attract the attention of capitalists, and bears evidence of such an indisputable character that oil does exist there in large quantities, that they do not hesitate to invest large amounts of money…” and so on.

On March 18, a letter is published in the Times from a professor and Government chemist in charge of the United States army laboratory in Philadelphia, written to the president of the Philadelphia and California Petroleum Company, in answer to the nay-saying of State Geologists Whitney and Brewer. Prof. J.M. Maisch says: “I have examined the coal oil from California sent to me, and find it to have a specific gravity of .8629, and to be composed of Benzine [technical info follows; I will stick to the gist of his letter], Illuminating oil… and Lubricating oil… The lubricating oil is very dense, has a strong body, and is in this respect greatly superior to many of the lubricating coal oils on our market. It is of a dark brown color, and will answer well for heavy machinery. With comparatively little trouble and outlay, a great portion of it may be purified so as to answer for light machinery. The illuminating oil is very light in color, and is easily obtained entirely colorless, by treatment with acids… ”

In fact, the wells were showing every sign of competing with Pennsylvania’s finest. On June 10, 1865, a HT article titled “The First Shipment of Coal Oil from Humboldt County” says that six packages of from fifteen to twenty gallons each of coal oil from the well of the Union Mattole Oil Co. was heading for San Francisco by steamer, and represented the first shipment of crude oil from Humboldt. Owen Coy’s Humboldt Bay Region research showed him that the same Union Mattole Co. shipped out 850 gallons in August, 275 in September, and 650 in November of ’65.

All these Union names do get a little confusing; I used to wonder about it (were they all a bunch of radicals back then? Or did they just like peace and harmony?). No, it’s just that most of the settlers in Humboldt County were from the seafaring and timber-cutting areas of the Northeast, and the Civil War was raging back East. Owen Coy clued me in, and a glance through the Humboldt Times confirms the impression of local Union, or Northern, loyalty. Lincoln was quite their hero and his death was mourned at length in the pages of the local papers.

Once in a while, the paper detoured from sheer boosterism to a more solemn exploration of questions of mining rights, laws, and government policies. On May 6, 1865, the HT discusses the debate between claims of miners vs. those of preemption homesteaders. It interprets a provision in a recently passed act of Congress as “explicitly recognizing a title, possessory though it may be, in the miner sufficient to protect him against interference… a ‘miner’s title’ properly perfected, is good and effectual until determined by the Government in whom the paramount title is, as against any and every other… these lands will not be subject to preemption nor disposed of in the manner prescribed for the disposal of public lands in ordinary cases.” Then appears a quote from a letter of instruction from the U.S. Department of the Interior to the Register and Receiver of the Humboldt Land District: “It is not the policy of the Government to deal with petroleum tracts as ordinary public lands… hence, you will report the exact description of any and all tracts strictly of the character you mention and, will withhold the same from disposal by the Government unless otherwise specifically instructed.”

If I’m not mistaken, all this mysterious language means that oil is much bigger business than homesteading, and the Government is not about to uphold the claims of settlers to land that might usually be granted as State School Lands or other “free land,” if miners wish to develop it for oil extraction.

The descriptions of the Mining Districts are quite specific in this regard. The language for the Frazier Mining District’s Laws, HT of 5/6/1865, is similar to most of the others’: “Whereas, the Territory embraced in this Mining District, hereinafter described, is totally unfit for agricultural purposes [??!!], therefore be it Resolved, that this shall be known as the Frazier Mining District, and shall be bounded as follows, to wit: Commencing at the northeast corner of the Mattole Mining District on Bear River, running thence due east until it [meets the Eel River, following upstream the] Eel River to the mouth of Bull Creek (opening into the South Fork of Eel River), thence up the head of Bull Creek, thence in a southerly direction to the upper crossing of Mattole River, thence down the Mattole River until it strikes the southeast line of Mattole Mining District.” An article of the Rules and Regulations says, “The locators, M.J. Conklin and Lieut. Frazier, of this District, shall be entitled to one extra claim of two thousand six hundred and forty feet square, for the right of discovery, to be divided between them, and it shall be known as the ‘Locators Claim’.”

Lt. Frazier, by the way, was in the Valley because he had been sent in the fall of 1863 to the fort at Upper Mattole by the Government to help put down the Indian threat. Another public figure prominent in the incorporation of oil companies and private roadbuilding companies was Col. S.G. Whipple, who was in charge of all the military forces committed to the Indian Wars in this district in 1864, according to Owen Coy (pp. 190-191). It is interesting that the oil exploration had pretty well ceased from 1861 until restarting in late 1864, as soon as the “Indian threat” had been removed by these enterprising men.

One thing leads to another

All this optimistic activity suggested commercial success in a much wider arena than simple oil profits themselves. Building the town of Petrolia was proceeding as quickly as possible. There was a sawmill on the Mill Creek off Lighthouse Road, once owned by John and Susan Clark, and deeded to George Hill in 1862. The piece, in Section 16, includes “a slab house and a two story frame saw mill, and machinery therein… ” The August, 1865, HT relates that “It is impossible to obtain lumber and shingles to do anything here in the way of building, the quantity manufactured at present being scarcely sufficient to supply the wants of the numerous companies now engaged in boring wells for oil. Mr. Geo. Hill and others are engaged in converting the old water power mill into a steam saw mill, which, when completed, it is believed, will be able to make good the deficiency in this respect, and to supply the demand in future. The tug ‘Mary Anne’ has made two or three attempts to land a cargo on the coast opposite this locality, but up to the present time has been unsuccessful. A brick-yard is in operation here, and a lively little place would soon spring up if there was anything to build with.”

Stores were wanted, and supplies to stock them. In late March of ’65, just after the surveying of the new town, J.W. Henderson’s diary reveals that he agreed to sell Ryan the store in Petrolia for $300, or rent it for $7 a month. The businessman was Pierce (or Pearce) H. Ryan, later “The Hon.,” a prominent Eureka figure. His enterprise was at the northwest corner of Front and Sherman Streets, near the present Petrolia Store.

According to Moses Conklin’s journal, about this time H.H. Buhne went into business here as well, and put G.E. Schumacher in charge as clerk; whether or not this was at the same location as the late-60s store owned by Schumacher facing the south side of the square (near where the pink-stone cemetery marker is now), we don’t know but might assume. It’s hard to tell from the deed descriptions or lack of them, as Henderson owned all the pieces to begin with and encouraged such tenants or buyers as he felt were needed for a flourishing town. So oftentimes the pieces were still in his name, no matter who was operating upon them.

The need for roads and /or ocean landing sites was sore. On July 16, Henderson says that Buhne and two steamers tried to land lumber and shingles, but that the landing was a failure. Two days later, Henderson received 400 shakes hauled overland by Gillette. By July 27, he is showing Parsons the mouth of the Mattole as a landing possibility, but “Parsons doesn’t think favorably of it as a harbor.” It’s a problem; there was a Bassett’s Landing mentioned by Henderson, and I once saw a map showing it roughly just below Peter B. Gulch (whether it was at the mouth of Peter B. or closer to the Mattole was not clear); but successful deliveries there were not common.

Much heavy hauling was done by horse or mule teams; on May 23, Henderson was loading machinery for the drilling site at Joel’s Flat (shipped from San Francisco by Geo. Noble) onto Gillette’s teams; the next day the men came to the Camp at the Flat, but it was three days later that the machinery arrived at Benjamin Smith’s. A couple of times that month Henderson mentions “examining the country for a road into Joel’s Flat”… but found it “impractable for present.”

Plank and Turnpike roads to the oil fields

There was great motivation for building “a good plank and turnpike road, to connect the oil-bearing districts in the lower part of this county with Humboldt Bay… the road as we all know is a necessity to the great oil interests of Humboldt, and it cannot be constructed too soon… The company has a right to expect that citizens will favor the work in all convenient ways, to the end that the great interest–oil–of the county may be developed at an early day,” as the HT urges on July 15, 1865. The article happens to speak of the Eel River and Mattole Plank and Turnpike Road Company, but there were several companies formed in succession, all with the same intention of making a privately-funded route suitable for large teams and hauling in and out of the Mattole and Bear River oil-producing country.

The original papers of incorporation for these enterprises–the Eel River and Mattole, the Petrolia and Centerville, and the Salt River and Mattole Plank and Turnpike Road Companies–are some of those given to the M.V.H.S. this summer by Ferndale Books. The first, which I’ll abbreviate the ER & M P & T Road Co., describes a proposed route south from “near the Van Aernam House near Table Bluff, running thence in a south-easterly direction, crossing Eel River at Davis’ ford, or some point below said ford and above ferry of R.M. Dungan, Esq., thence in the same general direction to the foot of the ‘divide’ between Bear River and Eel River; thence ascending to the ‘divide’ by the most practicable route to the summit of Bear river ridge; thence to a crossing on Bear river near the residence of Richard Johnson, Esq. [sic–Johnston is meant], thence ascending the ‘divide’ between the Bear and Mattole rivers to the summit; thence on the easiest grade to a place known as Petrolia.”

Sixteen subscribers to the corporation include J.S. Murray, J.E. Wyman, Joseph Russ, S.G. Whipple, C.S. Ricks, John Vance, and J.W. Henderson.

The description for the Petrolia and Centerville Plank and Turnpike Road Co.’s proposed route starts here: “…to commence at Petrolia, thence ascending the table land toward Wright’s claim, on the easiest and best grade; thence to Cook’s claim; thence in a westerly direction to the McNutt Gulch and following down the same to its mouth; thence along the coast to Singley’s Gulch; thence up the ridge on the north side of said gulch to the summit of the ‘divide’ between said gulch and Bear River; thence to Cassen and O’Dales [O’dell’s?]; thence to the summit of Bear river ridge… ” This route follows much the same path as today’s. And the company’s subscribers were the same men as for the previous organization. There is no notice that one group superceded the other, but apparently each fine-tuned the surveying a little more.

The third, or Salt River and Mattole, P & T Road Co. goes straight overland from Bear River “over the dividing ridge to Joel’s Flat, thence by the most practicable route over the divide to the claim of the Union Mattole Mining Company.” This route would generally follow the old Indian or horse trail from Bear River to the North Fork.

According to Coy, the actual road was not finished until 1869, and included a stretch along the beach from below Guthrie Creek (near False Cape, above Bear River) to Centerville, west of Ferndale. During the 1880’s, Chinese labor built that section of the Wildcat from Bear River Ridge north over the top to Ferndale. But already by 1871 a daily stage ran between Eureka and Petrolia on the two-year-old road.

Competition from unheard-of places

The route out of Petrolia “ascending the table land toward Wright’s claim” is generally the same road we follow up onto the Table and out past the eucalyptus trees toward Salladays’ (more recently Dennis Handy’s) and Devoys’ places. Lucian and Lucy Ann Wright’s original homestead claim was on the Devoy place; their quarter-section of land, the middle of the east half of Section 32, excluded a 150′ by 80′ piece “conveyed to Anderson,” according to their Homestead Registration. I have wondered what that lot was for, and recently found out: a deed from October 12, 1866, from Lucien Wright and wife to Henry Anderson and Michael Johnson, in exchange for $1 (even then merely a token), grants “… a certain piece… of land, lying and being situate in the town of Augusta, County of Humboldt… and more particularly described as follows, to wit: Commencing at a point on the northern side of Broadway Street or what is now a part and portion of the road leading from Petrolia to the coast… thence running easterly along said street eighty feet, thence northerly and at right angles with said street one hundred and fifty feet,… [etc., describing a square on north side of road] on which [the parties Anderson and Johnson] have erected a tavern and on what they are now residing, the house standing five feet easterly of westerly line of the lot as hereinbefore described… ” This tavern was known as Anderson’s Hotel.

So the Wrights were living in, or were envisioning living in, a town called Augusta, and the main street of it was Broadway–our road out of Petrolia. They were perhaps in a sort of competition with Henderson; a clause in the deed expressly prohibits oil prospecting on the Anderson property, and indeed sounds adamant in its opposition to such activity. J.W. Henderson’s journal entry of June 13, 1865, says “Sawmill PO & Co have an… opposition town on the table.” Now, “on the table” could merely mean “planned,” but it looks as if here it refers to an actual planned development on the Table. (What is Sawmill PO & Co? A complete mystery.)

Augusta was indeed a lively place. A letter in the HT of May 28, 1866, reports that “The ball at Anderson’s Hotel passed off very pleasantly; the ladies were pretty and agreeable, the dancing excellent, and the music and supper ditto. As a whole it was a creditable affair.”

But then the “opposition town” could have been something other than Augusta. A notice in the HT of September 9, 1865, tells us, “As Mr. Frederick Lewis… was riding on the road between Petrolia and Oil City, in Mattole, he was assaulted by Indians, or men disguised as such… ” (Clearly the latter, by that date.) But Oil City??

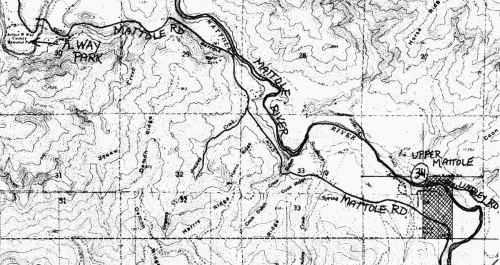

Part of an informative map found at HSU’s Humboldt Room.

So much to learn!

We have barely touched the tip of the iceberg as concerns Henderson’s journal and its revelations about the town he set up, as well as all his adventures trying to extract oil from Joel Flat. My notes for significant entries to consult in his journal go something like this (omitting most of the dates here)… “Bartlett’s machine arrived at Mattole… Gave Ben Smith a deed for land above Jerusalem… Funeral of President Lincoln… Moved camp to Joel’s Flat with Cook’s mules… Raised derricks for oil well in the Flat… Deed to T. Scott, req. of Parsons, for 2760 acres Mattole… (7/4) Read Declaration of Independence to crowd. Dull… Deeded Harwood blacksmith’s lot, in exchange for blacksmith work… Stopped at Anderson’s for dinner… Brought two kegs of oil to Petrolia, burned it in lamps. Almost drowned. Big frollick in town… Had Murray make a plot of town of Petrolia for Noble to take East… Broke Pittman rod and had to stop pumping oil… Engine pump froze up… ”

Please come in to the office to look over our transcription of Henderson’s journal. Future years (he kept it until 1910–although he was in Eureka much of that time) will probably be coming our way soon.

The information from the Recorder’s Office is less accessible, but more exact. I found there many of the lot sales in Petrolia to merchants and servicepeople, from J.W. Henderson. On October 1, 1866, he deeded, for the requisite $1, the corner lot of Lincoln and Henderson Streets to C.W. Gillette, Elmore Harrow, Joshua Betts, William Roberts, and David Willey, trustees of the United Brethren in Christ of Petrolia, “in trust for the use and benefit of said church.” To this day, that property is a church site–it went from the United Brethren, to being called the Community Church, to the Methodist Episcopalians (who built the present building around 1915) and in the 1920s to the Seventh-Day Adventists.

Waking up from a wild dream

The oil never came in large enough quantities to be called a success. Over the decades, there have been several resurgences of oil interest, but they have all disappointed the optimistic entrepreneur. Apparently our geology is too shaley and fractured to hold large, clean pools of oil, even though it’s clear that the oil is there. By June, 1866, a schoolteacher named Lane complained, “Petrolia is now a rather dry place… most of the people are much discouraged in regard to oil.”

By the summer of 1868, Moses Conklin wrote to the paper, “We have had quite an accession to our population this Spring, and a large number of strangers have visited our Valley during the past month, looking at the country with a view of settlement among us, with their families; many have expressed themselves highly pleased with our Valley, with the climate, water, etc.” Not a word about petroleum.

And by 1875, ten years after all the excitement, an anonymous letter writer defended the Valley against a slur evidently regarding its lack of sophistication. I think we might guess at the writer’s identity as Judge Conklin again: “In a financial point of view, it is true, we have not many very wealthy individuals, but as a community we are comfortable, and have very few what might be called poor people. I do not know of more than two places which are mortgaged… It is safe to say that no portion of Humboldt County or California surpasses our beautiful valley in natural resources, picturesque and attractive scenery and a fine invigorating climate.” He goes on at length in this vein, stressing the virtues of the Valley as an agricultural paradise; and again, no mention of oil.

~~~~~~~~

However, there were repeated attempts over the decades to wrest oil wealth from local earth. Next I will post Nicole Log’s report on developments subsequent to the 1860s.

Honeydew oil derrick, 1920s. From the Hindley Family collection at the MVHS.

And if the topic of oil exploration in the Mattole Valley interests you highly, check the other entries under “Oil Prospects” in the right hand column of topics on the home page here. The review of Ken Aalto’s talk on the possibilities of modern-day fracking is very relevant.

Also, an investigation into the granting, then swindling, of Chippewa and Sioux scrip for Mattole oil lands led to a dark and fascinating episode of American history that I reported in Issue #44 of Now… and Then. The article fleshes out many of the characters and business details reported in J.W. Henderson’s journal (and a couple of the blog entries here augment that!). Please comment if you would like me to send you a .pdf of that story.

~~~~~~~~

Here’s an excerpt from the autobiography of Shell Oil Vice-President Monroe Spaght, who was a Eureka native. He was the keynote speaker at the 1955 dedication of the Oil Wells plaque on the square in downtown Petrolia:

And here is the program from that event:

Finally, a few familiar faces: locals and schoolkids attending the dedication, 65 years ago this fall. Mr. Spaght is at the microphone.

Read Full Post »